Why the Agricultural Future Will Be Programmed in Code (English Version)

Agriculture is no longer just about soil, sun, and rain — today, it’s also about data, algorithms, and lines of code. In a world of volatile costs and uncertain climate, programming (or knowing how to interpret model results) is a true competitive advantage. This is not a call to replace traditional skills; it’s a call to enhance them: a farmer, an agricultural economist, and an agricultural engineer who know how to handle data can make better and faster decisions.

1) Evidence of the Digital Shift

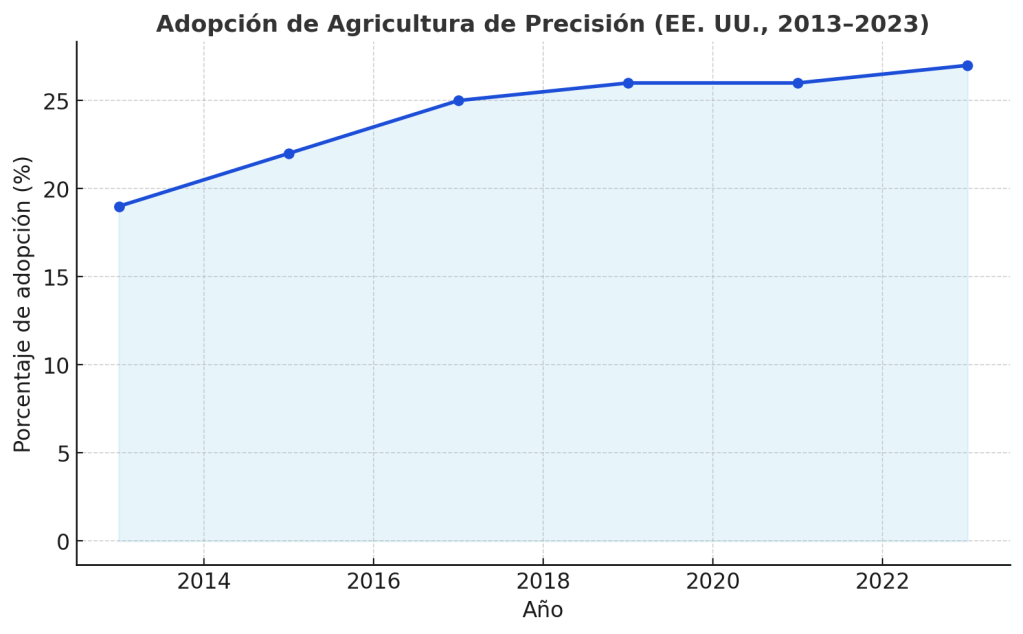

- In the United States, the adoption of precision agriculture technologies is growing, but disparities remain: only 27% of farms reported using at least one precision practice in 2023 (ARMS/USDA). Adoption increases with farm size, meaning that the larger the farm, the more likely it is to have implemented this type of system.

- The digitalization of agriculture (through sensors, automation, and software) is one of the most significant structural transformations since the mechanization of the 20th century, according to data from the ERS/USDA.

- The digital skills gap remains an obstacle in rural areas, which is why organizations such as the FAO promote technological literacy programs in agriculture (Digital Technologies in Agriculture and Rural Areas, 2022).

2) The New Language of Agriculture: Python, R, and SQL

Today, understanding the field means understanding the data. It’s no longer enough to observe the color of the soil or the size of the leaf — now we analyze graphs, spectral indices, and predictive models. In this digital era, Python, R, and SQL have become the new tools of modern agriculture. With these languages, it’s possible to build models that predict yields, estimate water demand, identify pests through satellite imagery, optimize production costs, and much more.

- Precision agriculture, which is based on measuring, observing, and applying inputs in a differentiated way, depends entirely on the ability to process data.

- The use of NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index), derived from satellite imagery, makes it possible to assess plant vigor and water stress, typically processed using Python and GIS libraries.

- Sensors installed on machinery and in fields (measuring moisture, protein, yield, etc.) collect information that must be analyzed through code in order to make precise irrigation or fertilization decisions.

With these tools, an agricultural economist can build models that anticipate international prices, detect logistical inefficiencies, or project the return on investment for each crop. An agricultural engineer can automate irrigation systems, connect sensors, or predict pests using artificial intelligence. Both professionals now share a common new language: code.

Python and R enable them to model production scenarios, conduct econometric or yield analyses, and automate complex calculations. SQL gives them control over large databases containing information on prices, yields, soils, and climate — allowing them to query, clean, and structure data with precision.

This shift does not mean replacing agricultural experience — it amplifies it. The professional who understands programming doesn’t just describe what happened on their farm; they predict what will happen and act in advance.

3) The Gap Between Agricultural Policy and Technology

For a long time, agricultural policies revolved around subsidies, credit programs, minimum prices, and tariffs. But the 21st century demands something more: policies that recognize that the true competitive advantage is now digital.

- Many support programs have never taken into account data platforms, rural connectivity, or training in data science.

- In the United States, only 27% of farms use precision practices (GAO, 2024).

- High initial costs and the lack of infrastructure (rural internet, sensors, training) are real barriers to adopting these technologies.

For local farmers to take advantage of the shift toward “digital agriculture,” policies must:

- Finance technological capital (sensors, drones, weather stations).

- Promote training in data analysis and partnerships with technology incubators.

- Establish public agricultural data platforms (climate, soils, prices).

- Offer smart subsidies that reward efficient management, not just production volume.

4) Programming Is Planning: Code as a Strategic Advantage

Take a look at this example:

- A farmer enters their farm’s parameters (soil type, yield history, climatic data), and a Python model tells them: “This area will require 20% more water tomorrow.”

- A system cross-references international market data with climate forecasts to suggest which crop to plant in the next season.

- Moisture sensors send automatic alerts to your phone or any device and trigger irrigation when soil moisture falls below a certain threshold.

This is not science fiction — this is reality. There are already autonomous tractors and agricultural robots that operate through code and computer vision systems. The farmer who programs is not “leaving agriculture”; they are building their competitive advantage in a world where differentiation is measured in bits. Because it’s no longer enough to simply produce — one must produce better, with fewer errors, and greater adaptability.

Conclusion

The agricultural future will not be written solely on a spreadsheet — it will be enhanced by code. Those who master these lines, even if they are not experts (and they don’t have to be), will be able to read their land like a data book, anticipate problems, respond with precision, and avoid losses in their agricultural business. In the coming years, success will depend less on the land you own and more on the information you can translate into well-analyzed decisions. Because in the agriculture of tomorrow, those who interpret their data best will cultivate the best future.

The Official Sponsor of this article is:

De Mi Tierra a Mi Pueblo Corp. 🌱 Committed to Agriculture and Food Security in Puerto Rico.

References

- USDA-ERS. Precision Agriculture in the Digital Era (EIB-248, 2023).

- GAO (2024). Precision Agriculture — adopción y barreras (27 % de fincas con PA).

- USDA-ERS Charts of Note (10 dic 2024): adopción aumenta con tamaño de finca.

- NASA Earthdata — NDVI, medición satelital de vigor vegetal.

- ASABE, Resource Magazine (2024): automatización, GNSS y máquinas conectadas.

- FAO. Digital Technologies in Agriculture and Rural Areas (2022).

October 4, 2025